Open Source Threat Hunting

Threat Hunting 101

Threat hunting: so hot right now.

It’s no secret attackers are constantly looking for new techniques to evade detection. To be an effective threat hunter, you need to leverage your experience, tools, and training to proactively detect these attacks. Many of us have been fortunate enough to attend extensive training provided by our organizations; however, the open source community can be one of the best places to learn new skills or hone existing ones.

Summary

This post will primarily focus on defining threat hunting, distinguishing its purpose from other SOC functions, and outlining basic hunting methodologies.

I’m sure you’re thinking “Wow, another blog post defining threat hunting? How many times can we continue to going over basics?” For me, the answer is that right now the limit does not exist. Unfortunately, there are still many misconceptions about the definition and purpose of a threat hunting program. Case in point: according to the 2019 SANS Threat Hunting Survey, 40% of respondents were still using a variety of reactive approaches and 57% were operating using Indicators of Compromise (IOCs) via an alerting system to find adversary tools or artifacts. Are these inherently bad security practices? No. But is operating out of a SIEM and responding to IOCs threat hunting? Also no.

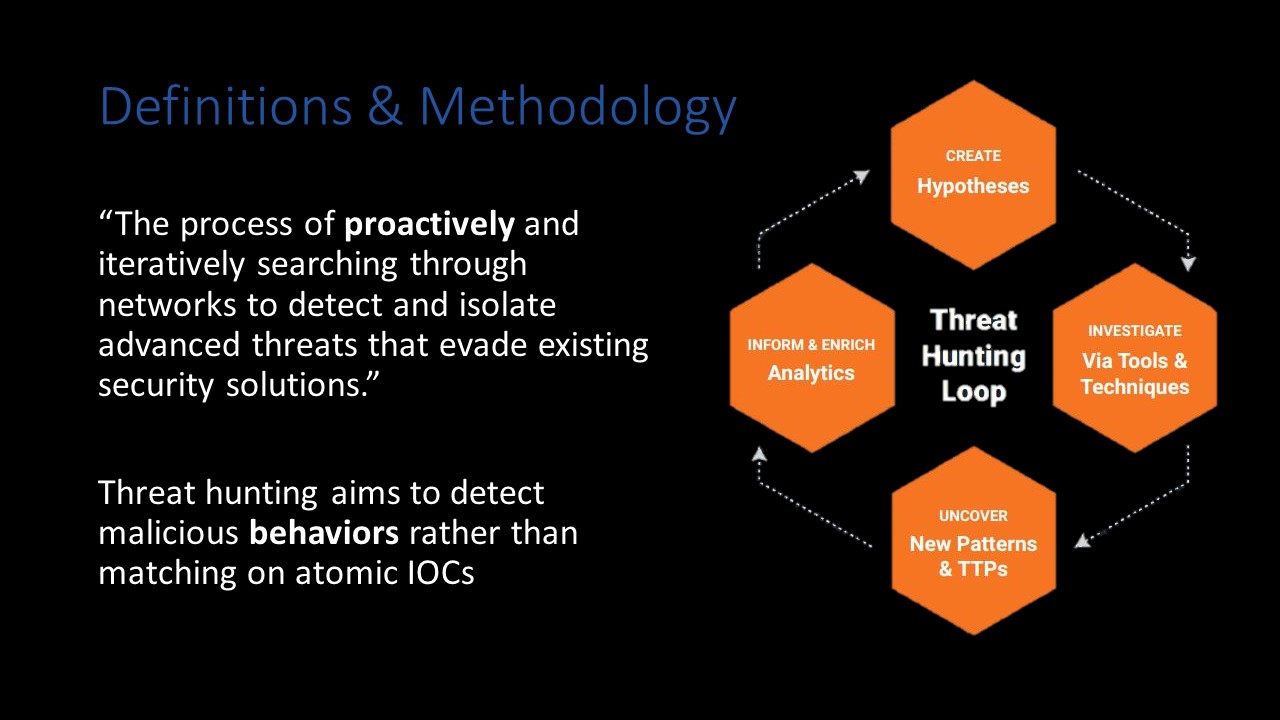

Definitions and Methodology

The key takeaway here is that your threat hunts should be aimed at proactively searching for malicious behavior that has (so far) evaded detection in your environment. You are essentially operating as a human SIEM sifting through and correlating data sources in search of anomalies. To avoid just aimlessly “looking for bad”, I recommend adhering to the Sqrrl Threat Hunting Model:

- Create Hypothesis

- Investigate Via Tools & Techniques

- Uncover New Patterns & TTPs

- Inform & Enrich Analytics

This methodology provides an easily repeatable process for threat hunting that still allows for some flexibility in execution.

I’d especially like to emphasize the Inform & Enrich Analytics step. The bottom line is your threat hunts are effectively worthless if you aren’t feeding your results back into other areas of your organization and improving your security posture. If you’ve executed a successful hunt and identified a gap in your detection capabilities you need to address these deficiencies.

Proactive vs Reactive

Proactive? Reactive? Does it matter? Yes. This highlights the distinct difference in launch points between threat hunting and incident response.

Think of your incident responders as firefighters and your threat hunters as police officers. Generally, incident responders are set in motion by a “fire” and operate nonstop until the incident is remediated; threat hunters, however, actively patrol the neighborhood looking for signs of attack and respond as needed.

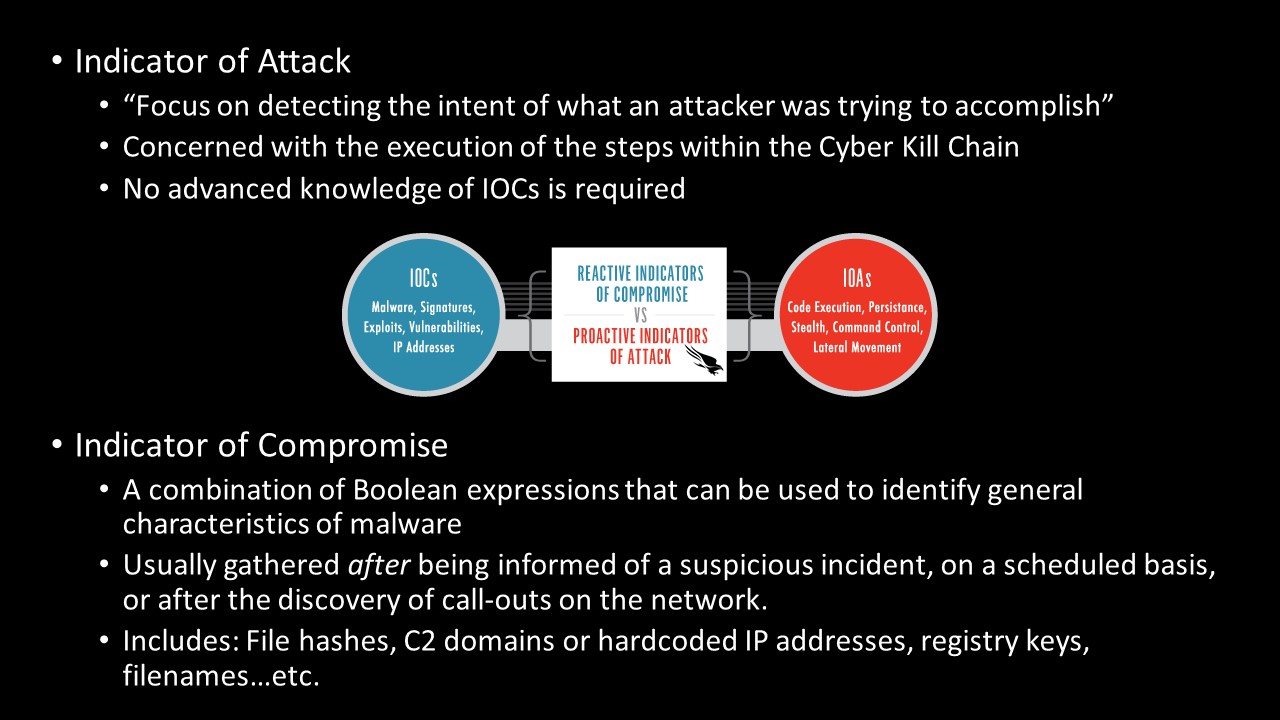

IOCs and IOAs

Just to get a bit deeper in the weeds CrowdStrike denotes the following difference between Indicators of Compromise and Indicators of Attack:

In evidence from a previous robbery CCTV allowed us to identify that the bank robber drives a purple van, wears a Baltimore Ravens cap and uses a drill and liquid nitrogen to break into the vault. Though we try to track and observe these unique characteristics, his modus operandi (MO), what happens when the same individual instead drives a red car and wears a cowboy hat and uses a crowbar to access the vault? The result? The robber is successful again because we, the surveillance team, relied on indicators that reflected an outdated profile (IOCs).

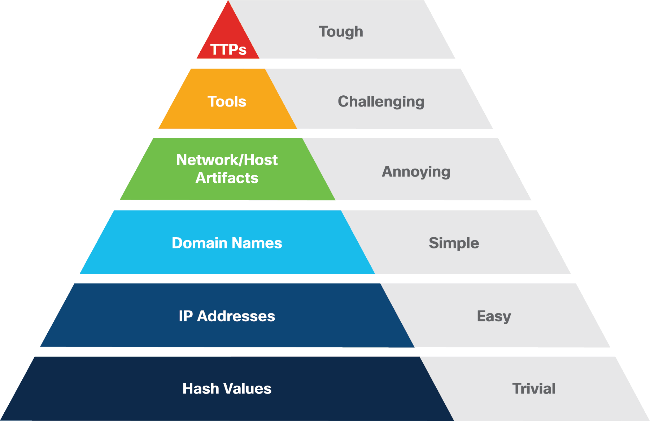

The easiest way to distinguish between the two is to divide the Pyramid of Pain (below) in half: Indicators of Compromise will likely consist of hash values, IP addresses, and domain names whereas Indicators of Attack will be network/host artifacts, tools, and tactics, techniques, and procedures (TTPs). I will caveat this by saying that network and host artifacts can deal with both IOCs and IOAs depending on several different factors. For example, a filename or hash alone are IOCs while an IOA would be a combination of Windows Event Logs detailing an intrusion.

The analogy they use ultimately boils down to looking for specific combinations of activity that indicate attacker presence rather than atomic IOCs. At this point it’s laughably easy to alter hashes, domains, IPs, and filenames…threat hunters must be able to reliably detect attackers despite these superficial changes. Focusing your efforts on developing methods to track and identify the upper half of the pyramid allows you to do just that.

The SOC Puzzle

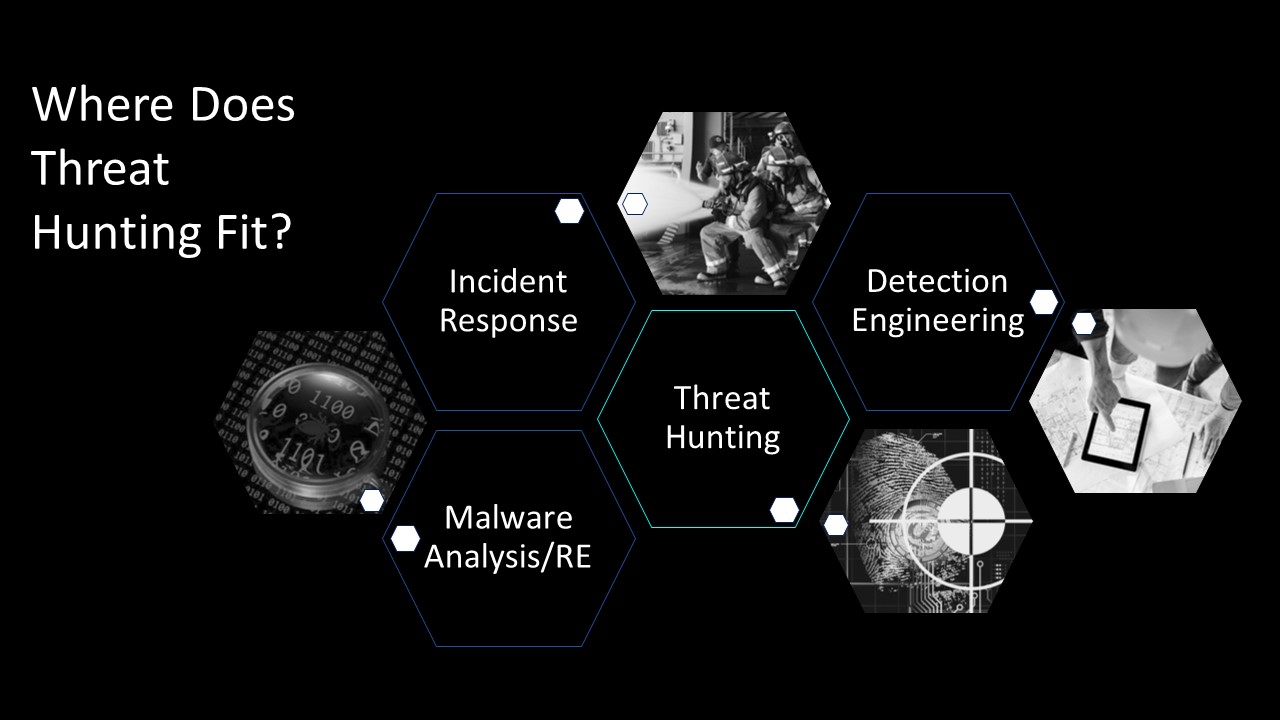

All of the above begs the question “Where does threat hunting fit in my organization?” Threat hunters, incident responders, malware analysts and reverse engineers, and detection engineers are all pieces that come together to form a fully functional Security Operations Center (SOC).

Threat hunters, if employed correctly, are the linchpin in an organization. A good threat hunting team should be feeding their hunt results to their detection engineers to help lower false positive rates, thus reducing overall mean time to detect and respond to incidents.

The Secret Ingredients

Based on personal experience the most effective threat hunting teams are composed of members who have a general baseline of knowledge in things like network communications and activity, network and host forensics, malware analysis, and memory forensics and bring some sort of specialty to the table. Whether that’s an Active Directory SME, a Windows Event Log guru, or some other specialty depends on your organization and, well, your personal interests.

To be an effective threat hunter I also strongly recommend brushing up on your investigative and incident response skills, as you’ll likely need to determine root cause of any suspicious behavior you detect or potentially even respond to an active intrusion you find. Note: The ability to swap out your threat hunting hat for an incident response hat will likely depend on your organization and how they divide roles and responsibilities.

Non-technical skills that are just as valuable include soft skills, written and oral communication, and attention to detail. It never hurts to be a naturally curious person either, though this is moreso a personality trait rather than a skill you can develop. Curiosity can be a double-edged sword if you have a tendency to find yourself lost in rabbit holes, as noted below:

“The challenge, though, like with all forensics, is to know when you are truly done and the hunter should move on. The analyst always will feel like he missed something or didn’t have the right skills to find it, or the adversary is simply better than him. No amount of searching will help remove the doubt that comes with hunting and not finding anything of substance. A good hunt team manager will constantly need to nudge analysts on to the next artifact to look for.”

Leveraging the Open Source DFIR Community

The DFIR community has a huge online presence. The photo above barely scratches the surface. I’ve also compiled a more robust list of resources that I’ll continue to update in the future.

As silly as it sounds, I can’t recommend Twitter enough. Seriously, go make a Twitter account and follow other DFIR people. So many people post links to their blogs, useful white papers, proofs of concepts, and drop hints about potential zero-days they’ve found. In my opinion it’s one of the better places to get relevant security information directly from the exploiters and investigators.